Types of Breathing While Striking in the Martial Arts

| Chinese martial arts | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武術 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武术 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "martial technique" | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

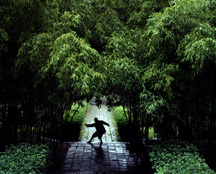

A monk practicing kung fu in the bamboo forest inside the Shaolin Temple

Chinese martial arts, oft called by the umbrella terms kung fu (; Chinese: 功夫; pinyin: gōngfu ; Cantonese Yale: gūng fū ), kuoshu (國術; guóshù ) or wushu (武術; wǔshù ), are multiple fighting styles that have developed over the centuries in Greater Mainland china. These fighting styles are oft classified according to common traits, identified as "families" of martial arts. Examples of such traits include Shaolinquan (少林拳) physical exercises involving All Other Animals (五形) mimicry or training methods inspired by Erstwhile Chinese philosophies, religions and legends. Styles that focus on qi manipulation are chosen internal ( 内家拳 ; nèijiāquán ), while others that concentrate on improving musculus and cardiovascular fitness are chosen external ( 外家拳 ; wàijiāquán ). Geographical association, equally in northern ( 北拳 ; běiquán ) and southern ( 南拳 ; nánquán ), is another pop nomenclature method.

Terminology [edit]

Kung fu, wushu and "Tillage"are loanwords from Cantonese and Standard mandarin respectively that, in English, are used to refer to Chinese martial arts. However, the Chinese terms kung fu and wushu ( ![]() listen (Mandarin)(assist·info) ; Cantonese Yale: móuh seuht ) accept singled-out meanings.[1] The Chinese equivalent of the term "Chinese martial arts" would be Zhongguo wushu (Chinese: 中國武術; pinyin: zhōngguó wǔshù ) (Mandarin).

listen (Mandarin)(assist·info) ; Cantonese Yale: móuh seuht ) accept singled-out meanings.[1] The Chinese equivalent of the term "Chinese martial arts" would be Zhongguo wushu (Chinese: 中國武術; pinyin: zhōngguó wǔshù ) (Mandarin).

In Chinese, the term kung fu refers to any skill that is caused through learning or exercise. Information technology is a compound discussion equanimous of the words 功 (gōng) meaning "work", "achievement", or "merit", and 夫 (fū) which is a particle or nominal suffix with diverse meanings.

Wushu literally means "martial art". Information technology is formed from the 2 Chinese characters 武術 : 武 ( wǔ ), meaning "martial" or "military machine" and 術 or 术 ( shù ), which translates into "art", "discipline", "skill" or "method". The term wushu has as well become the name for the modern sport of wushu, an exhibition and total-contact sport of bare-handed and weapon forms (套路), adapted and judged to a set of artful criteria for points developed since 1949 in the Communist china.[2] [3]

Quánfǎ ( 拳法 ) is another Chinese term for Chinese martial arts. It ways "fist method" or "the law of the fist" (quán means "boxing" or "fist", and fǎ means "law", "way" or "method"), although as a compound term it usually translates every bit "boxing" or "fighting technique." The name of the Japanese martial fine art kempō is represented by the same hanzi characters.

History [edit]

The genesis of Chinese martial arts has been attributed to the need for self-defense, hunting techniques and military machine training in ancient China. Hand-to-hand gainsay and weapons practice were important in training ancient Chinese soldiers.[iv] [5]

Detailed knowledge about the country and evolution of Chinese martial arts became available from the Nanjing decade (1928–1937), as the Fundamental Guoshu Plant established past the Kuomintang regime made an attempt to compile an encyclopedic survey of martial arts schools. Since the 1950s, the People's Republic of China has organized Chinese martial arts equally an exhibition and full-contact sport under the heading of "wushu".

Legendary origins [edit]

According to fable, Chinese martial arts originated during the semi-mythical Xia Dynasty (夏朝) more than 4,000 years ago.[6] It is said the Yellowish Emperor (Huangdi) (legendary date of ascent 2698 BCE) introduced the primeval fighting systems to Mainland china.[7] The Yellow Emperor is described as a famous general who, before becoming Communist china's leader, wrote lengthy treatises on medicine, star divination and the martial arts. One of his main opponents was Chi You (蚩尤) who was credited every bit the creator of jiao di, a precursor to the modern art of Chinese wrestling.[viii]

Early history [edit]

The earliest references to Chinese martial arts are found in the Spring and Autumn Register (fifth century BCE),[ix] where a hand-to-hand gainsay theory, one that integrates notions of "difficult" and "soft" techniques, is mentioned.[10] A combat wrestling system called juélì or jiǎolì ( 角力 ) is mentioned in the Classic of Rites.[11] This combat system included techniques such as strikes, throws, joint manipulation, and force per unit area betoken attacks. Jiao Di became a sport during the Qin Dynasty (221–207 BCE). The Han History Bibliographies record that, past the Erstwhile Han (206 BCE – 8 CE), there was a distinction between no-holds-barred weaponless fighting, which it calls shǒubó ( 手搏 ), for which training manuals had already been written, and sportive wrestling, then known as juélì ( 角力 ). Wrestling is also documented in the Shǐ Jì, Records of the Grand Historian, written by Sima Qian (ca. 100 BCE).[12]

In the Tang Dynasty, descriptions of sword dances were immortalized in poems by Li Bai. In the Song and Yuan dynasties, xiangpu contests were sponsored past the imperial courts. The modern concepts of wushu were fully developed by the Ming and Qing dynasties.[13]

Philosophical influences [edit]

The ideas associated with Chinese martial arts inverse with the evolution of Chinese lodge and over time acquired some philosophical bases: Passages in the Zhuangzi ( 莊子 ), a Taoist text, pertain to the psychology and do of martial arts. Zhuang Zi, its eponymous writer, is believed to have lived in the quaternary century BCE. The Tao Te Ching, often credited to Lao Zi, is some other Taoist text that contains principles applicable to martial arts. According to one of the archetype texts of Confucianism, Zhou Li ( 周禮 ), Archery and charioteering were part of the "six arts" (Chinese: 六藝; pinyin: liu yi , including rites, music, calligraphy and mathematics) of the Zhou Dynasty (1122–256 BCE). The Art of War ( 孫子兵法 ), written during the 6th century BCE by Dominicus Tzu ( 孫子 ), deals directly with armed services warfare just contains ideas that are used in the Chinese martial arts.

Taoist practitioners have been practicing Tao Yin (physical exercises similar to Qigong that was ane of the progenitors to T'ai chi ch'uan) from equally early equally 500 BCE.[14] In 39–92 CE, "6 Capacity of Hand Fighting", were included in the Han Shu (history of the Quondam Han Dynasty) written by Pan Ku. Also, the noted md, Hua Tuo, equanimous the "Five Animals Play"—tiger, deer, monkey, bear, and bird, around 208 CE.[15] Taoist philosophy and their approach to health and do accept influenced the Chinese martial arts to a certain extent. Straight reference to Taoist concepts tin can be institute in such styles as the "Eight Immortals," which uses fighting techniques attributed to the characteristics of each immortal.[sixteen]

Southern and Northern dynasties (420–589 Advert) [edit]

Shaolin temple established [edit]

In 495 CE, a Shaolin temple was built in the Song mountain, Henan province. The first monk who preached Buddhism at that place was the Indian monk named Buddhabhadra (佛陀跋陀羅; Fótuóbátuóluó ), but chosen Batuo (跋陀) by the Chinese. There are historical records that Batuo's commencement Chinese disciples, Huiguang (慧光) and Sengchou (僧稠), both had exceptional martial skills.[ commendation needed ] For example, Sengchou'southward skill with the tin can staff is even documented in the Chinese Buddhist catechism.[ commendation needed ] After Buddhabadra, another Indian[17] monk, named Bodhidharma (菩提達摩; Pútídámó ), also known every bit Damo (達摩) by the Chinese, came to Shaolin in 527 CE. His Chinese disciple, Huike (慧可), was also a highly trained martial arts expert.[ citation needed ] There are implications that these first three Chinese Shaolin monks, Huiguang, Sengchou, and Huike, may have been war machine men earlier entering the monastic life.[18]

Shaolin and temple-based martial arts [edit]

The Shaolin style of kung fu is regarded as ane of the first institutionalized Chinese martial arts.[19] The oldest evidence of Shaolin participation in combat is a stele from 728 CE that attests to two occasions: a defense of the Shaolin Monastery from bandits around 610 CE, and their subsequent role in the defeat of Wang Shichong at the Boxing of Hulao in 621 CE. From the 8th to the 15th centuries, in that location are no extant documents that provide evidence of Shaolin participation in combat.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries, at least forty sources be to provide prove both that monks of Shaolin expert martial arts, and that martial practice became an integral element of Shaolin monastic life. The earliest appearance of the oft cited legend concerning Bodhidharma's supposed foundation of Shaolin Kung Fu dates to this menstruum.[twenty] The origin of this fable has been traced to the Ming period's Yijin Jing or "Muscle Change Classic", a text written in 1624 attributed to Bodhidharma.

Depiction of fighting monks demonstrating their skills to visiting dignitaries (early 19th-century mural in the Shaolin Monastery).

References of martial arts practise in Shaolin announced in various literary genres of the belatedly Ming: the epitaphs of Shaolin warrior monks, martial-arts manuals, military encyclopedias, historical writings, travelogues, fiction, and verse. All the same, these sources exercise not point out whatever specific style that originated in Shaolin.[21] These sources, in contrast to those from the Tang menses, refer to Shaolin methods of armed combat. These include a skill for which Shaolin monks became famous: the staff (gùn, Cantonese gwan). The Ming General Qi Jiguang included a clarification of Shaolin Quan Fa (Chinese: 少林拳法; Wade–Giles: Shao Lin Ch'üan Fa ; lit. 'Shaolin fist technique'; Japanese: Shorin Kempo) and staff techniques in his book, Ji Xiao Xin Shu ( 紀效新書 ), which can translate as New Book Recording Constructive Techniques. When this book spread beyond East Asia, it had a great influence on the evolution of martial arts in regions such as Okinawa[22] and Korea.[23]

Modernistic history [edit]

Republican menses [edit]

Virtually fighting styles that are being practiced as traditional Chinese martial arts today reached their popularity within the 20th century. Some of these include Baguazhang, Drunken Boxing, Hawkeye Claw, 5 Animals, Xingyi, Hung Gar, Monkey, Bak Mei Pai, Northern Praying Mantis, Southern Praying Mantis, Fujian White Crane, Jow Ga, Wing Chun and Taijiquan. The increase in the popularity of those styles is a result of the dramatic changes occurring within the Chinese gild.

In 1900–01, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists rose against foreign occupiers and Christian missionaries in China. This uprising is known in the West as the Boxer Rebellion due to the martial arts and calisthenics practiced by the rebels. Empress Dowager Cixi gained control of the rebellion and tried to use it against the foreign powers. The failure of the rebellion led ten years later to the autumn of the Qing Dynasty and the creation of the Chinese Commonwealth.

The present view of Chinese martial arts is strongly influenced by the events of the Republican Period (1912–1949). In the transition period betwixt the fall of the Qing Dynasty as well as the turmoil of the Japanese invasion and the Chinese Civil War, Chinese martial arts became more attainable to the general public as many martial artists were encouraged to openly teach their art. At that time, some considered martial arts as a ways to promote national pride and build a strong nation. As a result, many training manuals (拳譜) were published, a training academy was created, two national examinations were organized and demonstration teams traveled overseas.[24] Numerous martial arts associations were formed throughout China and in various overseas Chinese communities. The Central Guoshu Academy (Zhongyang Guoshuguan, 中央國術館) established past the National Authorities in 1928[25] and the Jing Wu Able-bodied Association (精武體育會) founded by Huo Yuanjia in 1910 are examples of organizations that promoted a systematic approach for training in Chinese martial arts.[26] [27] [28] A series of provincial and national competitions were organized past the Republican government starting in 1932 to promote Chinese martial arts. In 1936, at the 11th Olympic Games in Berlin, a grouping of Chinese martial artists demonstrated their art to an international audition for the outset fourth dimension.

The term kuoshu (or guoshu, 國術 meaning "national art"), rather than the vernacular term gongfu was introduced past the Kuomintang in an effort to more closely acquaintance Chinese martial arts with national pride rather than individual achievement.

People's Democracy [edit]

Chinese martial arts experienced rapid international dissemination with the finish of the Chinese Ceremonious War and the founding of the People'due south Republic of Communist china on Oct i, 1949. Many well known martial artists chose to escape from the Cathay's rule and migrate to Taiwan, Hong Kong,[29] and other parts of the globe. Those masters started to teach within the overseas Chinese communities only eventually they expanded their teachings to include people from other ethnic groups.

Inside China, the exercise of traditional martial arts was discouraged during the turbulent years of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1969–1976).[3] Like many other aspects of traditional Chinese life, martial arts were subjected to a radical transformation by the People's Democracy of China to align them with Maoist revolutionary doctrine.[three] The PRC promoted the committee-regulated sport of Wushu every bit a replacement for independent schools of martial arts. This new contest sport was disassociated from what was seen as the potentially destructive self-defense aspects and family lineages of Chinese martial arts.[3]

In 1958, the government established the All-China Wushu Clan every bit an umbrella organization to regulate martial arts training. The Chinese Land Commission for Physical Culture and Sports took the lead in creating standardized forms for most of the major arts. During this period, a national Wushu system that included standard forms, teaching curriculum, and instructor grading was established. Wushu was introduced at both the high school and academy level. The suppression of traditional teaching was relaxed during the Era of Reconstruction (1976–1989), as Communist ideology became more accommodating to alternative viewpoints.[30] In 1979, the State Committee for Concrete Culture and Sports created a special task strength to reevaluate the didactics and exercise of Wushu. In 1986, the Chinese National Research Plant of Wushu was established as the central authority for the research and assistants of Wushu activities in the Cathay.[31]

Irresolute government policies and attitudes towards sports, in general, led to the closing of the State Sports Commission (the central sports authority) in 1998. This closure is viewed as an attempt to partially de-politicize organized sports and move Chinese sport policies towards a more market place-driven approach.[32] Every bit a result of these changing sociological factors inside China, both traditional styles and modernistic Wushu approaches are beingness promoted by the Chinese government.[33]

Chinese martial arts are an integral chemical element of 20th-century Chinese popular culture.[34] Wuxia or "martial arts fiction" is a popular genre that emerged in the early 20th century and peaked in popularity during the 1960s to 1980s. Wuxia films were produced from the 1920s. The Kuomintang suppressed wuxia, accusing it of promoting superstition and vehement anarchy. Considering of this, wuxia came to flourish in British Hong Kong, and the genre of kung fu movie in Hong Kong action cinema became wildly popular, coming to international attention from the 1970s. The genre underwent a drastic pass up in the tardily 1990s as the Hong Kong film industry was crushed by economic depression.

In the wake of Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), at that place has been somewhat of a revival of Chinese-produced wuxia films aimed at an international audience, including Zhang Yimou's Hero (2002), Firm of Flight Daggers (2004) and Curse of the Aureate Bloom (2006), as well as Su Chao-pin and John Woo's Reign of Assassins (2010).

Styles [edit]

China has a long history of martial arts traditions that includes hundreds of different styles. Over the past 2 thousand years, many distinctive styles have been adult, each with its own fix of techniques and ideas.[35] There are as well common themes to the different styles, which are oftentimes classified past "families" ( 家 ; jiā ), "sects" ( 派 ; pai ) or "schools" ( 門 ; men ). At that place are styles that mimic movements from animals and others that gather inspiration from diverse Chinese philosophies, myths and legends. Some styles put most of their focus into the harnessing of qi, while others concentrate on competition.

Chinese martial arts can be split into diverse categories to differentiate them: For example, external ( 外家拳 ) and internal ( 內家拳 ).[36] Chinese martial arts can also be categorized past location, as in northern ( 北拳 ) and southern ( 南拳 ) too, referring to what part of People's republic of china the styles originated from, separated by the Yangtze River (長江); Chinese martial arts may even be classified according to their province or city.[24] The chief perceived difference between northern and southern styles is that the northern styles tend to emphasize fast and powerful kicks, loftier jumps and generally fluid and rapid movement, while the southern styles focus more on strong arm and hand techniques, and stable, immovable stances and fast footwork. Examples of the northern styles include changquan and xingyiquan. Examples of the southern styles include Bak Mei, Wuzuquan, Choy Li Fut, and Wing Chun. Chinese martial arts can also exist divided co-ordinate to faith, imitative-styles ( 象形拳 ), and family styles such every bit Hung Gar ( 洪家 ). There are distinctive differences in the grooming between unlike groups of the Chinese martial arts regardless of the type of classification. Still, few experienced martial artists make a clear stardom betwixt internal and external styles, or subscribe to the idea of northern systems being predominantly kicking-based and southern systems relying more heavily on upper-body techniques. Most styles contain both hard and soft elements, regardless of their internal nomenclature. Analyzing the difference in accordance with yin and yang principles, philosophers would assert that the absence of either one would render the practitioner's skills unbalanced or scarce, as yin and yang alone are each only half of a whole. If such differences did once be, they take since been blurred.

Grooming [edit]

Chinese martial arts training consists of the following components: basics, forms, applications and weapons; different styles place varying emphasis on each component.[37] In addition, philosophy, ethics and even medical practice[38] are highly regarded past most Chinese martial arts. A consummate preparation system should too provide insight into Chinese attitudes and culture.[39]

Basics [edit]

The Basics ( 基本功 ) are a vital role of any martial training, as a student cannot progress to the more than advanced stages without them. Basics are usually made up of rudimentary techniques, conditioning exercises, including stances. Basic grooming may involve simple movements that are performed repeatedly; other examples of bones training are stretching, meditation, striking, throwing, or jumping. Without strong and flexible muscles, management of Qi or breath, and proper body mechanics, it is impossible for a pupil to progress in the Chinese martial arts.[forty] [41] A common saying concerning bones preparation in Chinese martial arts is every bit follows:[42]

内外相合,外重手眼身法步,内修心神意氣力。

Which translates every bit:

Railroad train both Internal and External. External training includes the hands, the optics, the body and stances. Internal preparation includes the heart, the spirit, the listen, breathing and force.

Stances [edit]

Stances (steps or 步法) are structural postures employed in Chinese martial arts training.[43] [44] [ self-published source? ] They correspond the foundation and the form of a fighter's base. Each style has unlike names and variations for each opinion. Stances may exist differentiated by foot position, weight distribution, trunk alignment, etc. Stance training can be practiced statically, the goal of which is to maintain the structure of the stance through a fix time period, or dynamically, in which instance a series of movements is performed repeatedly. The Horse opinion ( 騎馬步/馬步 ; qí mǎ bù/mǎ bù ) and the bow opinion are examples of stances found in many styles of Chinese martial arts.

Meditation [edit]

In many Chinese martial arts, meditation is considered to be an important component of basic training. Meditation can be used to develop focus, mental clarity and can act as a footing for qigong training.[45] [46]

Utilise of qi [edit]

The concept of qi or ch'i ( 氣 ) is encountered in a number of Chinese martial arts. Qi is variously defined every bit an inner free energy or "life force" that is said to animate living beings; as a term for proper skeletal alignment and efficient apply of musculature (sometimes likewise known as fa jin or jin); or every bit a autograph for concepts that the martial arts student might not yet be prepare to understand in total. These meanings are non necessarily mutually exclusive.[note 1] The existence of qi as a measurable class of free energy as discussed in traditional Chinese medicine has no basis in the scientific agreement of physics, medicine, biology or human physiology.[47]

There are many ideas regarding the control of i's qi energy to such an extent that it tin can be used for healing oneself or others.[48] Some styles believe in focusing qi into a unmarried betoken when attacking and aim at specific areas of the human body. Such techniques are known equally dim mak and have principles that are similar to acupressure.[49]

Weapons grooming [edit]

About Chinese styles also make apply of preparation in the broad armory of Chinese weapons for conditioning the torso as well as coordination and strategy drills.[l] Weapons grooming ( 器械 ; qìxiè ) is by and large carried out subsequently the student becomes proficient with the basic forms and applications grooming. The basic theory for weapons training is to consider the weapon as an extension of the body. It has the same requirements for footwork and body coordination as the basics.[51] The process of weapon training proceeds with forms, forms with partners and then applications. Virtually systems have training methods for each of the Eighteen Arms of Wushu( 十八般兵器 ; shíbābānbīngqì ) in addition to specialized instruments specific to the system.

Application [edit]

Application refers to the applied use of combative techniques. Chinese martial arts techniques are ideally based on efficiency and effectiveness.[52] [53] Application includes non-compliant drills, such as Pushing Hands in many internal martial arts, and sparring, which occurs within a variety of contact levels and dominion sets.

When and how applications are taught varies from style to style. Today, many styles begin to teach new students by focusing on exercises in which each student knows a prescribed range of combat and technique to drill on. These drills are often semi-compliant, pregnant 1 student does not offer active resistance to a technique, in social club to let its demonstrative, clean execution. In more than resisting drills, fewer rules apply, and students practice how to react and respond. 'Sparring' refers to a more than avant-garde format, which simulates a combat situation while including rules that reduce the chance of serious injury.

Competitive sparring disciplines include Chinese kickboxing Sǎnshǒu ( 散手 ) and Chinese folk wrestling Shuāijiāo ( 摔跤 ), which were traditionally contested on a raised platform arena, or Lèitái ( 擂台 ).[54] Lèitái were used in public challenge matches kickoff appeared in the Song Dynasty. The objective for those contests was to knock the opponent from a raised platform by any means necessary. San Shou represents the modern development of Lei Tai contests, just with rules in place to reduce the chance of serious injury. Many Chinese martial art schools teach or work within the rule sets of Sanshou, working to incorporate the movements, characteristics, and theory of their way.[55] Chinese martial artists likewise compete in non-Chinese or mixed Combat sport, including boxing, kickboxing and Mixed martial arts.

Forms [edit]

Forms or taolu (Chinese: 套路; pinyin: tàolù ) in Chinese are series of predetermined movements combined so they can be practiced as a continuous ready of movements. Forms were originally intended to preserve the lineage of a particular style branch, and were often taught to avant-garde students selected for that purpose. Forms independent both literal, representative and practise-oriented forms of applicable techniques that students could extract, exam, and train in through sparring sessions.[56]

Today, many consider taolu to be one of the nigh important practices in Chinese martial arts. Traditionally, they played a smaller role in training for combat application and took a back seat to sparring, drilling, and conditioning. Forms gradually build up a practitioner'southward flexibility, internal and external forcefulness, speed and stamina, and they teach balance and coordination. Many styles incorporate forms that use weapons of various lengths and types, using i or two easily. Some styles focus on a sure type of weapon. Forms are meant to be both practical, usable, and applicable as well equally to promote fluid motion, meditation, flexibility, balance, and coordination. Students are encouraged to visualize an attacker while preparation the class.

In that location are two general types of taolu in Chinese martial arts. Most common are solo forms performed by a unmarried student. In that location are likewise sparring forms — choreographed fighting sets performed by two or more people. Sparring forms were designed both to acquaint starting time fighters with bones measures and concepts of combat and to serve as performance pieces for the school. Weapons-based sparring forms are especially useful for teaching students the extension, range, and technique required to manage a weapon.

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts [edit]

The term taolu (套路) is a shortened version of Tao Lu Yun Dong (套路運動), an expression introduced only recently with the popularity of modern wushu. This expression refers to "exercise sets" and used in the context of athletics or sport.

In contrast, in traditional Chinese martial arts alternative terminologies for the training (練) of 'sets or forms are:

- lian quan tao (練拳套) – practicing a sequence of fists.

- lian quan jiao (練拳腳) – practicing fists and anxiety.

- lian bing qi (練兵器) – practicing weapons.

- dui da (對打) and dui lian (對練) – fighting sets.

Traditional "sparring" sets, called dui da (對打) or dui lian (對練), were an essential part of Chinese martial arts for centuries. Dui lian means, to train by a pair of combatants opposing each other—the graphic symbol lian (練), refers to practice; to train; to perfect one'due south skill; to drill. Also, often one of these terms are also included in the name of fighting sets (雙演; shuang yan), "paired practice" (掙勝; zheng sheng), "to struggle with strength for victory" (敵; di), match – the character suggests to strike an enemy; and "to break" (破; po).

Generally, in that location are 21, 18, 12, 9 or 5 drills or 'exchanges/groupings' of attacks and counterattacks, in each dui lian set. These drills were considered simply generic patterns and never meant to be considered inflexible 'tricks'. Students good smaller parts/exchanges, individually with opponents switching sides in a continuous flow. Dui lian were not merely sophisticated and constructive methods of passing on the fighting knowledge of the older generation, but they were likewise essential and effective grooming methods. The relationship betwixt single sets and contact sets is complicated, in that some skills cannot be developed with solo 'sets', and, conversely, with dui lian. Unfortunately, it appears that most traditional gainsay oriented dui lian and their training methodology accept disappeared, especially those concerning weapons. At that place are several reasons for this. In modern Chinese martial arts, most of the dui lian are recent inventions designed for light props resembling weapons, with rubber and drama in heed. The role of this kind of training has degenerated to the point of beingness useless in a applied sense, and, at best, is just operation.

By the early Vocal menses, sets were not and so much "individual isolated technique strung together" simply rather were composed of techniques and counter technique groupings. It is quite clear that "sets" and "fighting (2-person) sets" accept been instrumental in traditional Chinese martial arts for many hundreds of years—even before the Song Dynasty. There are images of two-person weapon training in Chinese rock painting going back at least to the Eastern Han Dynasty.

According to what has been passed on by the older generations, the approximate ratio of contact sets to single sets was approximately 1:3. In other words, about thirty% of the 'sets' practiced at Shaolin were contact sets, dui lian, and two-person drill training. This ratio is, in role, evidenced past the Qing Dynasty mural at Shaolin.

For most of its history, Shaolin martial arts was mostly weapon-focused: staves were used to defend the monastery, not blank hands. Even the more contempo military exploits of Shaolin during the Ming and Qing Dynasties involved weapons. According to some traditions, monks first studied basics for one year and were then taught staff fighting so that they could protect the monastery. Although wrestling has been equally sport in Prc for centuries, weapons accept been an essential part of Chinese wushu since ancient times. If one wants to talk nearly contempo or 'modern' developments in Chinese martial arts (including Shaolin for that matter), information technology is the over-emphasis on bare hand fighting. During the Northern Vocal Dynasty (976- 997 A.D) when platform fighting is known as Da Laitai (Championship Fights Claiming on Platform) first appeared, these fights were with only swords and staves. Although later, when bare hand fights appeared also, it was the weapons events that became the most famous. These open-ring competitions had regulations and were organized past government organizations; the public as well organized some. The regime competitions, held in the capital and prefectures, resulted in appointments for winners, to armed forces posts.

Exercise forms vs. kung fu in combat [edit]

Even though forms in Chinese martial arts are intended to draw realistic martial techniques, the movements are non always identical to how techniques would be practical in gainsay. Many forms accept been elaborated upon, on the one manus, to provide better gainsay preparedness, and on the other paw to look more aesthetically pleasing. One manifestation of this tendency toward elaboration beyond gainsay application is the employ of lower stances and higher, stretching kicks. These two maneuvers are unrealistic in combat and are used in forms for do purposes.[57] Many modern schools have replaced practical defense or crime movements with acrobatic feats that are more spectacular to picket, thereby gaining favor during exhibitions and competitions.[note two] This has led to criticisms past traditionalists of the endorsement of the more acrobatic, prove-oriented Wushu competition.[58] Historically forms were often performed for amusement purposes long earlier the appearance of modernistic Wushu equally practitioners have looked for supplementary income by performing on the streets or in theaters. Documentation in ancient literature during the Tang Dynasty (618–907) and the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1279) suggests some sets, (including two + person sets: dui da too called dui lian) became very elaborate and 'flowery', many mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the signal that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire category of martial arts known equally Hua Fa Wuyi. During the Northern Song period, information technology was noted past historians this type of training had a negative influence on grooming in the military.

Many traditional Chinese martial artists, as well as practitioners of modernistic sport gainsay, have get critical of the perception that forms work is more relevant to the fine art than sparring and drill application, while most continue to run across traditional forms do inside the traditional context—every bit vital to both proper gainsay execution, the Shaolin aesthetic as an art form, too every bit upholding the meditative function of the physical fine art form.[59]

Another reason why techniques often appear different in forms when contrasted with sparring application is thought by some to come up from the darkening of the actual functions of the techniques from outsiders.[lx] [ self-published source? ]

Forms exercise is more often than not known for didactics gainsay techniques yet when practicing forms, the practitioner focuses on posture, animate, and performing the techniques of both right and left sides of the body.[61]

Wushu [edit]

Modern forms are used in the sport of wushu, as seen in this staff routine

The word wu ( 武 ; wǔ ) means "martial". Its Chinese grapheme is made of two parts; the first pregnant "walk" or "stop" ( 止 ; zhǐ ) and the second meaning "lance" ( 戈 ; gē ). This implies that "wu 武" is a defensive apply of combat.[ dubious ] The term "wushu 武術" significant "martial arts" goes back as far equally the Liang Dynasty (502–557) in an anthology compiled by Xiao Tong ( 蕭通 ), (Prince Zhaoming; 昭明太子 d. 531), called Selected Literature ( 文選 ; Wénxuǎn ). The term is plant in the second verse of a verse form by Yan Yanzhi titled: 皇太子釋奠會作詩 "Huang Taizi Shidian Hui Zuoshi".

"The great homo grows the many myriad things . . .

Breaking away from the armed forces arts,

He promotes fully the cultural mandates."

- (Translation from: Echoes of the Past past Yan Yanzhi (384–456))

The term wushu is also found in a verse form by Cheng Shao (1626–1644) from the Ming Dynasty.

The earliest term for 'martial arts' can be found in the Han History (206BC-23AD) was "military fighting techniques" ( 兵技巧 ; bīng jìqiǎo ). During the Song period (c.960) the name changed to "martial arts" ( 武藝 ; wǔyì ). In 1928 the name was changed to "national arts" ( 國術 ; guóshù ) when the National Martial Arts Academy was established in Nanjing. The term reverted to wǔshù under the People's Democracy of Communist china during the early 1950s.

Every bit forms have grown in complexity and quantity over the years, and many forms lone could be expert for a lifetime, modernistic styles of Chinese martial arts take developed that concentrate solely on forms, and do not practice application at all. These styles are primarily aimed at exhibition and competition, and often include more acrobatic jumps and movements added for enhanced visual result[62] compared to the traditional styles. Those who generally prefer to practice traditional styles, focused less on exhibition, are often referred to equally traditionalists. Some traditionalists consider the competition forms of today's Chinese martial arts every bit too commercialized and losing much of their original values.[63] [64]

"Martial morality" [edit]

Traditional Chinese schools of martial arts, such as the famed Shaolin monks, often dealt with the report of martial arts not just every bit a means of self-defense force or mental training, but equally a arrangement of ethics.[39] [65] Wude ( 武 德 ) can be translated equally "martial morality" and is constructed from the words wu ( 武 ), which ways martial, and de ( 德 ), which means morality. Wude deals with two aspects; "Virtue of deed" and "Virtue of mind". Virtue of human activity concerns social relations; morality of listen is meant to cultivate the inner harmony between the emotional listen ( 心 ; Xin ) and the wisdom mind ( 慧 ; Hui ). The ultimate goal is reaching "no extremity" ( 無 極 ; Wuji ) – closely related to the Taoist concept of wu wei – where both wisdom and emotions are in harmony with each other.

Virtues:

| Concept | Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin romanization | Yale Cantonese Romanization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humility | Qian | 謙 | 谦 | qiān | hīm |

| Virtue | Cheng | 誠 | 诚 | chéng | sìhng |

| Respect | Li | 禮 | 礼 | lǐ | láih |

| Morality | Yi | 義 | 义 | yì | yih |

| Trust | Xin | 信 | xìn | seun | |

| Concept | Proper name | Chinese | Pinyin romanization | Yale Cantonese Romanization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courage | Yong | 勇 | yǒng | yúhng |

| Patience | Ren | 忍 | rěn | yán |

| Endurance | Heng | 恆 | héng | hàhng |

| Perseverance | Yi | 毅 | yì | ngaih |

| Volition | Zhi | 志 | zhì | ji |

Notable practitioners [edit]

Examples of well-known practitioners ( 武術名師 ) throughout history:

- Yue Fei (1103–1142 CE) was a famous Chinese general and patriot of the Vocal Dynasty. Styles such as Eagle Claw and Xingyiquan attribute their cosmos to Yue. However, there is no historical bear witness to support the claim he created these styles.

- Ng Mui (belatedly 17th century) was the legendary female founder of many Southern martial arts such as Wing Chun, and Fujian White Crane. She is oft considered one of the legendary Five Elders who survived the devastation of the Shaolin Temple during the Qing Dynasty.

- Yang Luchan (1799–1872) was an important teacher of the internal martial art known as t'ai chi ch'uan in Beijing during the second half of the 19th century. Yang is known as the founder of Yang-mode t'ai chi ch'uan, as well as transmitting the fine art to the Wu/Hao, Wu and Dominicus t'ai chi families.

- Ten Tigers of Canton (late 19th century) was a grouping of ten of the tiptop Chinese martial arts masters in Guangdong (Canton) towards the terminate of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). Wong Kei-Ying, Wong Fei Hung's begetter, was a member of this group.

- Wong Fei Hung (1847–1924) was considered a Chinese folk hero during the Republican catamenia. More ane hundred Hong Kong movies were made nearly his life. Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan, and Jet Li accept all portrayed his grapheme in blockbuster pictures.

- Huo Yuanjia (1867–1910) was the founder of Chin Woo Athletic Association who was known for his highly publicized matches with foreigners. His biography was recently portrayed in the movie Fearless (2006).

- Ip Man (1893–1972) was a master of the Fly Chun and the start to teach this fashion openly. Yip Human being was the instructor of Bruce Lee. Nigh major branches of Wing Chun taught in the Westward today were developed and promoted by students of Yip Man.

- Gu Ruzhang (1894–1952) was a Chinese martial artist who disseminated the Bak Siu Lum (Northern Shaolin) martial arts system across southern China in the early 20th century. Gu was known for his expertise in Iron Palm paw workout among other Chinese martial art training exercises.

- Bruce Lee (1940–1973) was a Chinese-American martial artist and actor who was considered an important icon in the 20th century.[66] He skilful Wing Chun and made it famous. Using Fly Chun as his base and learning from the influences of other martial arts his experience exposed him to, he subsequently adult his own martial arts philosophy that evolved into what is at present called Jeet Kune Do.

- Jackie Chan (b. 1954) is the famous Hong Kong martial artist, film actor, stuntman, action choreographer, managing director and producer, and a global popular culture icon, widely known for injecting physical comedy into his martial arts performances, and for performing complex stunts in many of his films.

- Jet Li (b. 1963) is the five-time sport wushu champion of Communist china, afterwards demonstrating his skills in picture palace.

- Donnie Yen (b. 1963) is a Hong Kong thespian, martial artist, film manager and producer, action choreographer, and globe wushu tournament medalist.

- Wu Jing (b. 1974) is a Chinese actor, managing director, and martial artist. He was a member of the Beijing wushu team. He started his career every bit action choreographer and later equally an actor.

In pop culture [edit]

References to the concepts and use of Chinese martial arts tin be found in popular civilisation. Historically, the influence of Chinese martial arts tin be plant in books and in the performance arts specific to Asia.[67] Recently, those influences have extended to the movies and television that targets a much wider audience. As a effect, Chinese martial arts take spread beyond its indigenous roots and have a global appeal.[68] [69]

Martial arts play a prominent function in the literature genre known as wuxia ( 武俠小說 ). This type of fiction is based on Chinese concepts of chivalry, a separate martial arts society ( 武林 ; Wulin ) and a cardinal theme involving martial arts.[70] Wuxia stories can exist traced equally far dorsum as second and 3rd century BCE, becoming popular past the Tang Dynasty and evolving into novel form by the Ming Dynasty. This genre is still extremely popular in much of Asia[71] and provides a major influence for the public perception of the martial arts.

Martial arts influences tin also be found in dance, theater [72] and especially Chinese opera, of which Beijing opera is ane of the best-known examples. This pop grade of drama dates back to the Tang Dynasty and continues to be an example of Chinese culture. Some martial arts movements can be found in Chinese opera and some martial artists tin be found as performers in Chinese operas.[73]

In mod times, Chinese martial arts have spawned the genre of picture palace known as the Kung fu film. The films of Bruce Lee were instrumental in the initial burst of Chinese martial arts' popularity in the West in the 1970s.[74] Bruce Lee was the iconic international superstar that popularized Chinese martial arts in the West with his own variation of Chinese martial arts called Jeet Kune Do. It is a hybrid style of martial art that Bruce Lee proficient and mastered. Jeet Kune Do is his very ain unique style of martial art that uses little to minimum movement only maximizes the effect to his opponents. The influence of Chinese martial fine art take been widely recognized and have a global appeal in Western cinemas starting off with Bruce Lee.

Martial artists and actors such as Jet Li and Jackie Chan accept continued the appeal of movies of this genre. Jackie Chan successfully brought in a sense of humour in his fighting manner in his movies. Martial arts films from China are often referred to as "kung fu movies" ( 功夫片 ), or "wire-fu" if extensive wire work is performed for special effects, and are still best known every bit part of the tradition of kung fu theater. (see as well: wuxia, Hong Kong action movie theatre). The talent of these individuals have broadened Hong Kong's cinematography product and rose to popularity overseas, influencing Western cinemas.

In the due west, kung fu has go a regular action staple, and makes appearances in many films that would non generally exist considered "Martial Arts" films. These films include only are not express to The Matrix franchise, Impale Nib, and The Transporter.

Martial arts themes can also be found on boob tube networks. A U.S. network Boob tube western series of the early on 1970s called Kung Fu as well served to popularize the Chinese martial arts on television. With threescore episodes over a three-yr span, it was one of the first North American Television set shows that tried to convey the philosophy and practise in Chinese martial arts.[75] [76] The employ of Chinese martial arts techniques can now be found in most Idiot box action serial, although the philosophy of Chinese martial arts is seldom portrayed in depth.

Influence on hip hop [edit]

In the 1970s, Bruce Lee was start to gain popularity in Hollywood for his martial arts movies. The fact that he was a non-white male who portrayed self-reliance and righteous self-subject field resonated with black audiences and made him an important figure in this community.[77] Around 1973, Kung Fu movies became a hit in America across all backgrounds; even so, black audiences maintained the films' popularity well afterwards the general public lost involvement. Urban youth in New York Metropolis were still going from every borough to Time Foursquare every night to spotter the latest movies.[78] Amongst these individuals were those coming from the Bronx where, during this fourth dimension, hip-hop was beginning to have course. One of the pioneers responsible for the development of the foundational aspects of hip-hop was DJ Kool Herc, who began creating this new form of music past taking rhythmic breakdowns of songs and looping them. From the new music came a new course of dance known equally b-boying or breakdancing, a manner of street dance consisting of improvised acrobatic moves. The pioneers of this dance credit kung fu as one of its influences. Moves such as the crouching low leg sweep and "up rocking" (continuing gainsay moves) are influenced by choreographed kung-fu fights.[79] The dancers' power to improvise these moves led way to battles, which were dance competitions between two dancers or crews judged on their inventiveness, skills, and musicality. In a documentary, Crazy Legs, a fellow member of breakdancing group Rock Steady Coiffure, described the breakdancing battle being like an old kung fu movie, "where the 1 kung fu principal says something along the lines of 'hun your kung fu is good, merely mine is better,' then a fight erupts." [79]

Hip hop group Wu Tang Clan were prominently influenced by kung fu cinema. The proper noun "Wu Tang" itself is a reference to the 1983 film Shaolin and Wu Tang. Subsequent albums past the grouping (especially their debut album Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)) are rich with references to kung fu films of the 1970s and 1980s, which group members grew upward watching. Several group members (Ghostface Killah, Ol' Muddied Bastard, Method Man, and Masta Killa) had besides taken their phase names from kung fu movie theater. Several music videos, promotional photos, etc. feature group members posing or engaging with kung fu regalia and action sequences.

Meet also [edit]

- Eighteen Artillery of Wushu

- Difficult and soft (martial arts)

- Kung fu (disambiguation)

- List of Chinese martial arts

- Wushu (sport)

- Kwoon

- Weapons and armor in Chinese mythology

Notes [edit]

- ^ Pages 26–33[24]

- ^ Pages 118–119[56]

References [edit]

- ^ Jamieson, John; Tao, Lin; Shuhua, Zhao (2002). Kung Fu (I): An Elementary Chinese Text. The Chinese University Press. ISBN978-962-201-867-9.

- ^ Cost, Monroe (2008). Owning the Olympics: Narratives of the New Cathay. Chinese University of Michigan Press. p. 309. ISBN978-0-472-07032-9.

- ^ a b c d Fu, Zhongwen (2006) [1996]. Mastering Yang Way Taijiquan. Louis Swaine. Berkeley, California: Blueish Serpent Books. ISBN1-58394-152-5.

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (October 2000). Warfare in Chinese History. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 328. ISBN90-04-11774-1.

- ^ Graff, David Andrew; Robin Higham (March 2002). A Armed services History of China. Westview Printing. pp. 15–16. ISBN0-8133-3990-1. Peers, C.J. (2006-06-27). Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC–1840 Advertising . Osprey Publishing. p. 130. ISBN1-84603-098-6.

- ^ Greenish, Thomas A. (2001). Martial arts of the earth: an encyclopedia . ABC-CLIO. pp. 26–39. ISBN978-ane-57607-150-two.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1993-05-15). Asian Mythologies. trans. Wendy Doniger. University Of Chicago Press. p. 246. ISBN0-226-06456-5.

- ^ Zhongyi, Tong; Cartmell, Tim (2005). The Method of Chinese Wrestling. North Atlantic Books. p. 5. ISBN978-one-55643-609-3.

- ^ "Journal of Asian Martial Arts Volume 16". Periodical of Asian Martial Arts. Via Media Pub. Co., original from Indiana Academy: 27. 2007. ISSN 1057-8358.

- ^ trans. and ed. Zhang Jue (1994), pp. 367–370, cited after Henning (1999) p. 321 and annotation 8.

- ^ Classic of Rites. Affiliate half-dozen, Yuèlìng. Line 108.

- ^ Henning, Stanley E. (Fall 1999). "Academia Encounters the Chinese Martial arts" (PDF). China Review International. 6 (2): 319–332. doi:10.1353/cri.1999.0020. ISSN 1069-5834. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2020-07-20 .

- ^ Sports & Games in Ancient China (China Spotlight Series). China Books & Periodicals Inc. December 1986. ISBN0-8351-1534-8.

- ^ Lao, Cen (Apr 1997). "The Evolution of T'ai Chi Ch'uan". The International Magazine of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. Wayfarer Publications. 21 (2). ISSN 0730-1049.

- ^ Dingbo, Wu; Patrick D. Murphy (1994). Handbook of Chinese Pop Civilization. Greenwood Press. p. 156. ISBN0-313-27808-3.

- ^ Padmore, Penelope (September 2004). "Druken Fist". Black Chugalug Magazine. Active Involvement Media: 77.

- ^ Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21972-4. p. 8.

- ^ Canzonieri, Salvatore (February–March 1998). "History of Chinese Martial arts: Jin Dynasty to the Period of Disunity". Han Wei Wushu. 3 (ix).

- ^ Christensen, Matthew B. (2016-11-15). A Geek in Cathay: Discovering the Country of Alibaba, Bullet Trains and Dim Sum. Tuttle Publishing. p. 40. ISBN978-1462918362.

- ^ Shahar, Meir (2000). "Epigraphy, Buddhist Historiography, and Fighting Monks: The Case of The Shaolin Monastery". Asia Major. 3rd Serial. 13 (2): xv–36.

- ^ Shahar, Meir (December 2001). "Ming-Period Bear witness of Shaolin Martial Do". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 61 (2): 359–413. doi:10.2307/3558572. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 3558572. S2CID 91180380.

- ^ Kansuke, Yamamoto (1994). Heiho Okugisho: The Clandestine of Loftier Strategy. W.M. Hawley. ISBN0-910704-92-9.

- ^ Kim, Sang H. (January 2001). Muyedobotongji: The Comprehensive Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts of Ancient Korea. Turtle Press. ISBN978-i-880336-53-three.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Brian; Elizabeth Guo (2005-xi-11). Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Due north Atlantic Books. ISBN1-55643-557-half-dozen.

- ^ Morris, Andrew (2000). National Skills: Guoshu Martial arts and the Nanjing Country, 1928–1937. 2000 AAS Annual Coming together, March 9–12, 2000. San Diego, CA, U.s.. Archived from the original on 2011-04-04. Retrieved 2008-06-04 .

- ^ Brownell, Susan (1995-08-01). Training the Body for Mainland china: sports in the moral society of the people's republic. Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN0-226-07646-6.

- ^ Mangan, J. A.; Fan Hong (2002-09-29). Sport in Asian Society: Past and Present. Uk: Routledge. p. 244. ISBN0-7146-5342-X.

- ^ Morris, Andrew (2004-09-13). Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Civilization in Republican China. University of California Printing. ISBN0-520-24084-seven.

- ^ Amos, Daniel Miles (1986) [1983]. Marginality and the Hero's Fine art: Martial artists in Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton). University of California at Los Angeles: University Microfilms International. p. 280. ASIN B00073D66A. Retrieved 2011-12-07 .

- ^ Kraus, Richard Brusk (2004-04-28). The Party and the High-sounding in Mainland china: The New Politics of Culture (State and Lodge in Eastern asia). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 29. ISBN0-7425-2720-four.

- ^ Bin, Wu; Li Xingdong; Yu Gongbao (1995-01-01). Essentials of Chinese Wushu. Beijing: Strange Languages Press. ISBNseven-119-01477-3.

- ^ Riordan, Jim (1999-09-xiv). Sport and Physical Education in Red china. Spon Press (United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland). ISBN0-419-24750-5. p.xv

- ^ Minutes of the 8th IWUF Congress Archived 2007-06-fourteen at the Wayback Machine, International Wushu Federation, December 9, 2005 (accessed 01/2007)

- ^ Zhang, Wei; Tan Xiujun (1994). "Wushu". Handbook of Chinese Pop Culture. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. pp. 155–168. 9780313278082.

- ^ Yan, Xing (1995-06-01). Liu Yamin, Xing Yan (ed.). Treasure of the Chinese Nation—The Best of Chinese Wushu Shaolin Kung fu (Chinese ed.). Communist china Books & Periodicals. ISBNvii-80024-196-3.

- ^ Tianji, Li; Du Xilian (1995-01-01). A Guide to Chinese Martial Arts. Foreign Languages Printing. ISBN7-119-01393-9.

- ^ Liang, Shou-Yu; Wen-Ching Wu (2006-04-01). Kung Fu Elements. The Manner of the Dragon Publishing. ISBNane-889659-32-0.

- ^ Schmieg, Anthony L. (December 2004). Watching Your Dorsum: Chinese Martial Arts and Traditional Medicine. University of Hawaii Printing. ISBN0-8248-2823-2.

- ^ a b Hsu, Adam (1998-04-15). The Sword Polisher's Record: The Way of Kung-Fu (1st ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN0-8048-3138-6.

- ^ Wong, Kiew Kit (2002-11-xv). The Fine art of Shaolin Kung Fu: The Secrets of Kung Fu for Self-Defence force, Health, and Enlightenment. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN0-8048-3439-3.

- ^ Kit, Wong Kiew (2002-05-01). The Complete Volume of Shaolin: Comprehensive Program for Physical, Emotional, Mental and Spiritual Development. Creation Publishing. ISBN983-40879-1-viii.

- ^ Zhongguo da bai ke quan shu zong bian ji wei yuan hui "Zong suo yin" bian ji wei yuan hui, Zhongguo da bai ke quan shu chu ban she bian ji bu bian (1994). Zhongguo da bai ke quan shu (中国大百科全书总编辑委員会) [Baike zhishi (中国大百科, Chinese Encyclopedia)] (in Chinese). Shanghai:Xin hua shu dian jing xiao. p. 30. ISBNvii-5000-0441-9.

- ^ Mark, Bow-Sim (1981). Wushu basic training (The Chinese Wushu Research Institute volume series). Chinese Wushu Research Institute. ASIN B00070I1FE.

- ^ Wu, Raymond (2007-03-20). Fundamentals of High Functioning Wushu: Taolu Jumps and Spins. Lulu.com. ISBN978-ane-4303-1820-0.

- ^ Jwing-Ming, Yang (1998-06-25). Qigong for Health & Martial Arts, 2d Edition: Exercises and Meditation (Qigong, Health and Healing) (two ed.). YMAA Publication Center. ISBN1-886969-57-four.

- ^ Raposa, Michael Fifty. (November 2003). Meditation & the Martial Arts (Studies in Rel & Civilisation). University of Virginia Press. ISBN0-8139-2238-0.

- ^ Ernst, Edzard; Simon Singh (2009). Trick or treatment: The undeniable facts about alternative medicine. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN978-0393337785.

- ^ Cohen, Kenneth Due south. (1997). The Way Of Qigong: The Fine art And Scientific discipline Of Chinese Free energy Healing. Ballantine. ISBN0-345-42109-4.

- ^ Montaigue, Erle; Wally Simpson (March 1997). The Main Meridians (Encyclopedia Of Dim-Mak). Paladin Press. ISBNane-58160-537-4.

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming (1999-06-25). Aboriginal Chinese Weapons, Second Edition: The Martial Arts Guide. YMAA Publication Center. ISBNane-886969-67-ane.

- ^ Wang, Ju-Rong; Wen-Ching Wu (2006-06-13). Sword Imperatives—Mastering the Kung Fu and Tai Chi Sword. The Way of the Dragon Publishing. ISBN1-889659-25-eight.

- ^ Lo, Human Kam (2001-11-01). Police Kung Fu: The Personal Gainsay Handbook of the Taiwan National Police. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN0-8048-3271-iv.

- ^ Shengli, Lu (2006-02-09). Combat Techniques of Taiji, Xingyi, and Bagua: Principles and Practices of Internal Martial Arts. trans. Zhang Yun. Bluish Serpent Books. ISBNone-58394-145-2.

- ^ Hui, Mizhou (July 1996). San Shou Kung Fu Of The Chinese Ruby Army: Applied Skills And Theory Of Unarmed Combat. Paladin Printing. ISBN0-87364-884-6.

- ^ Liang, Shou-Yu; Tai D. Ngo (1997-04-25). Chinese Fast Wrestling for Fighting: The Art of San Shou Kuai Jiao Throws, Takedowns, & Ground-Fighting. YMAA Publication Centre. ISBNane-886969-49-3.

- ^ a b Bolelli, Daniele (2003-02-20). On the Warrior'due south Path: Philosophy, Fighting, and Martial Arts Mythology. Frog Books. ISBN1-58394-066-nine.

- ^ Kane, Lawrence A. (2005). The Way of Kata. YMAA Publication Heart. p. 56. ISBNi-59439-058-4.

- ^ Johnson, Ian; Sue Feng (August twenty, 2008). "Inner Peace? Olympic Sport? A Fight Brews". Wall Street Periodical. Retrieved 2008-08-22 .

- ^ Fowler, Geoffrey; Juliet Ye (Dec 14, 2007). "Kung Fu Monks Don't Become a Kick Out of Fighting". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-08-22 .

- ^ Seabrook, Jamie A. (2003). Martial Arts Revealed. iUniverse. p. xx. ISBN0-595-28247-iv.

- ^ Verstappe, Stefan (2014-09-04). "Three hidden meanings of Chinese forms". Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2019-04-12 .

- ^ Shoude, Xie (1999). International Wushu Competition Routines. Hai Feng Publishing Co., Ltd. ISBN962-238-153-7.

- ^ Parry, Richard Lloyd (August sixteen, 2008). "Kung fu warriors fight for martial fine art's futurity". London: Times Online. Retrieved 2008-08-22 .

- ^ Polly, Matthew (2007). American Shaolin: Flying Kicks, Buddhist Monks, and the Legend of Iron Crotch : an Odyssey in the New China . Gotham. ISBN978-one-59240-262-5.

- ^ Deng, Ming-dao (1990-12-nineteen). Scholar Warrior: An Introduction to the Tao in Everyday Life (1st ed.). HarperOne. ISBN0-06-250232-8.

- ^ Joel Stein (1999-06-xiv). "ТІМЕ 100: Bruce Lee". Time. Archived from the original on Jan 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-09 .

- ^ Mroz, Daniel (2012). The Dancing Word: An Embodied Approach to the Training of Performers and the Composition of Performances. Rodopi. ISBN978-9401200264.

- ^ Prashad, Vijay (2002-11-18). Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. Buoy Press. ISBN0-8070-5011-3.

- ^ Kato, M. T. (2007-02-08). From Kung Fu to Hip Hop: Globalization, Revolution, and Pop Culture (Suny Series, Explorations in Postcolonial Studies). Land University of New York Printing. ISBN978-0-7914-6992-7.

- ^ Denton, Kirk A.; Bruce Fulton; Sharalyn Orbaugh (2003-08-15). "Chapter 87. Martial-Arts Fiction and Jin Yong". In Joshua South. Mostow (ed.). The Columbia Companion to Modern East Asian Literature. Columbia University Press. pp. 509. ISBN0-231-11314-v.

- ^ Cao, Zhenwen (1994). "Affiliate 13. Chinese Gallant Fiction". In Dingbo Wu, Patrick D. Murphy (ed.). Handbook of Chinese Popular Civilisation. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 237. ISBN0313278083.

- ^ Mroz, Daniel (July 2009). "From Motion to Action: Martial Arts in the Practice of Devised Concrete Theatre". Practise of Devised Physical Theatre, Studies in Theatre and Operation. 29 (2).

- ^ Mroz, Daniel (2011-04-29). The Dancing Discussion: An Embodied Approach to the Preparation of Performers and the Composition of Performances. (Consciousness, Literature & the Arts). Rodopi. ISBN978-9042033306.

- ^ Schneiderman, R. Thou. (2009-05-23). "Contender Shores Up Karate's Reputation Amid U.F.C. Fans". The New York Times . Retrieved 2010-01-30 .

- ^ Pilato, Herbie J. (1993-05-15). Kung Fu Book of Caine (1st ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN0-8048-1826-6.

- ^ Carradine, David (1993-01-15). Spirit of Shaolin . Tuttle Publishing. ISBN0-8048-1828-2.

- ^ Phil Hoad, "Why Bruce Lee and kung fu films hit home with black audiences", The Guardian

- ^ Wisdom B, "Know Your Hip-Hop History: The B-Boy", Throwback Magazine

- ^ a b Chris Friedman, "Kung Fu Influences Aspects of Hip Hop Civilization Like Suspension Dancing"

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_martial_arts

Postar um comentário for "Types of Breathing While Striking in the Martial Arts"